The Art & Zen of Kumiko

by Matt Kenney

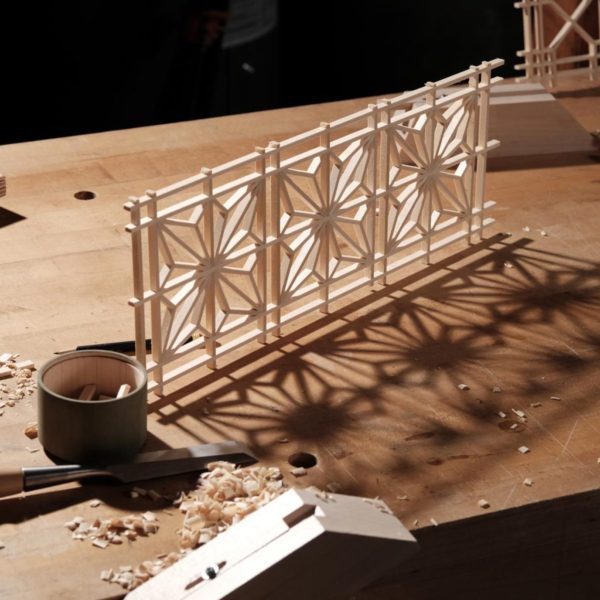

I have made many kumiko panels, and used it as a decorative element in boxes. I love the repetitive patterns of large panels, but am just as taken with a single hemp leaf pattern showcased on a cabinet door. It’s a gorgeous decorative detail. Including kumiko in your work can elevate it above the run of the mill furniture that fills most homes. The making of kumiko is very precise work and requires great perseverance. And it’s well worth learning for that reason alone. But there are other reasons as well.

The Zen of Kumiko

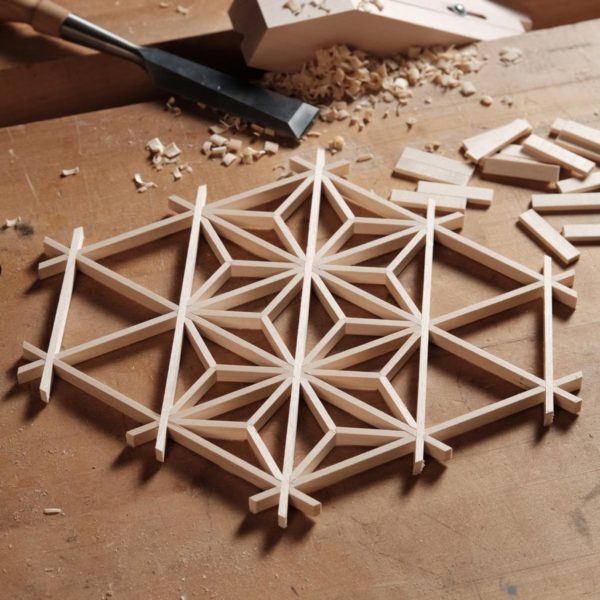

The process of making kumiko is quiet, deliberate, and enjoyable. It’s peaceful. While I love the precision of it, what I really like is sitting at my bench, cutting angles onto the ends of the tiny pattern pieces, and getting them all to fit together, with naught but friction holding them in place. It takes focus, the type of focus that liberates you from all your other concerns. There is a rhythm to the process that is almost hypnotic, and you certainly loose yourself in it. The chisel becomes an extension of your hand. What you think, it does. And what it does, you feel. There are times that I feel every fiber as it is cut by the chisel.

There is a powerful control in this feeling. There is also a deeper connection to the wood in it. When it is all going just right, a clarity comes to my mind, one in which I understand what I am doing at an intuitive level, and I can make the small adjustments that are sometimes needed without thinking about them, and without trial and error. I make the change and it’s spot on.

Having Patience

Kumiko is also a great way to develop patience and improve your attention in the shop. This is because the technical challenge of making kumiko, at least the patterns your most likely to start with, is not that great. The frame parts can be made quickly at the tablesaw with a finger joint jig. The pieces for the infill pattern are not tough to make either. A set of guides ensures that you pare the correct angles on the pieces’ ends. It is simple work. (It’s joyful work, too.) This means you don’t need to expend energy on the technical side of the process. In fact, to do well with kumiko you must be insanely focused not on the technical but on precision.

Certainly, there are things you can do in terms of technique to improve precision, but I’ve found that even the best technique falls short if you are not patient, and do not give your work attention. In this way, making kumiko is no different than making furniture (and so many other meaningful activities we undertake in life).

What does it mean to be patient? I think it’s allowing the work that you are doing to dictate the pace at which you do it. There’s a cadence, a rhythm to all the work we do in the shop. To be patient with your work you must consider each individual task and distill it, so that you see it’s essential components, so that you understand where you can work quickly, and where you must slow down.

You can cut tails very quickly, for example. Get that backsaw humming and knock them out. However, when it comes time to transfer the tails to the pin board (only savages cut pins first), you must slow down, get the boards aligned properly, hold the pencil or knife just right, and make a careful stroke. So, patience is always moving at the correct speed for the work you’re doing.

Paying Attention

Attention is just as important, and it’s not just a matter of being focused on the work at hand. You also must have a clear mind. If you’re thinking about how your mother-in-law always smells like cabbage, your thoughts and the actions that flow from them will be muddled. When you are paring angles on the infill pieces of the asa-no-ha pattern, there should be nothing in your mind, but your hand and how it holds the chisel, how it pushes the chisel through the small part beneath your fingers, the resistance the wood gives or doesn’t give, the sound made as its slices through the wood, etc. That level of attention enables you notice the smallest hiccup in the process, to notice minute blips that affect the precision of your work.

How to Develop Patience and Attention

So, the big question is how do you go about acquiring patience and attention? Attention is probably easier to develop. When you go into the shop, don’t start working right away. Put away the tools you left out last time. Sharpen a plane blade. Clean up your bench. Sweep the floor. Give your mind time to leave the world outside your shop. Patience comes through work. To truly understand a task like cutting dovetails or making tiny little boxes, you must cut dovetails and make tiny little boxes. And then do it some more, and, then, do it some more again. There is no shortcut here.There are no tricks. Perhaps that sounds daunting, but look at this way. You get to spend more time in the shop making furniture, boxes, spoons, bowls, or whatever. That’s a good thing. The world’s a better place when folks are using their heads and hands to make useful things.

OK, I’ll bring this all back around to kumiko now. Because there is a simplicity to the work, and because you can quickly knock out a panel, you can distill the process without much trouble, figuring out exactly what’s involved and how fast you can move. Making kumiko panels will help you develop patience. And the nature of the work helps to clear your mind, allowing you to give complete attention to the work. So, making kumiko will help you develop the two most important tools in the shop: patience and attention.

If you are interested in learning about Kumiko or taking a class with Matt Kenney check out the Florida School of Woodwork.

Matt Kenney

Matt Kenney has made things from wood his entire life. He made his first piece of furniture—a storage box for gardening supplies—more than15 years ago, in the attic above the duplex where he lived. It wasn’t much to look at, but making that box awoke a passion for making furniture, a passion that has driven him ever since. He’s made a lot of furniture since then, constantly striving to improve his craftsmanship and design. The result of his efforts is furniture that is modern but grounded in the best of classic design, able to sit harmoniously alongside a wide range of furniture styles, and built to survive generations of daily use.

Matt’s work has been featured on the cover of Fine Woodworking (the world’s leading furniture making magazine) three times. He’s also written several articles for the magazine.